Patient Presentation

A 7-year-old female came to clinic with a 2 day history of general fatigue. Initially she had a low grade fever of 100.5°F but this had increased over time to 101.8°F. She also was now drinking less and hadn’t urinated in 6 hours. Her father noted over the day she seemed to be having neck stiffness and was only wanting to hold her head tilted to the right. On her way to the clinic she complained of a minor sore throat. There was strep throat circulating in her school. The past medical history was non-contributory and she was fully immunized. The review of systems showed no rash, emesis/diarrhea, cough, dysphonia, difficulty opening/closing her mouth, or ear or neck pain.

The pertinent physical exam showed a moderately ill-child. Her temperature was 101.7°F, respiratory rate of 22, pulse of 124, and she had a normal blood pressure. She was fatigued and fussy but would cooperate with examination. She had full range of motion in her neck but did have a preference of a right head tilt. Her ears were normal. Her pharynx showed 2-3+ tonsils that were red without exudates or palatal petechiae. There was no asymmetry of the tonsillar pillars or uvula. No bulging was noted in the posterior pharynx. Her lips were slightly tacky. Her teeth showed no pain with tapping. Her neck had no obvious asymmetry and she had some anterior and posterior cervical shotty lymph nodes. Her neck had no palpable tenderness. Her heart, lungs and abdomen were negative. She had no rashes and her capillary refill was 3 seconds

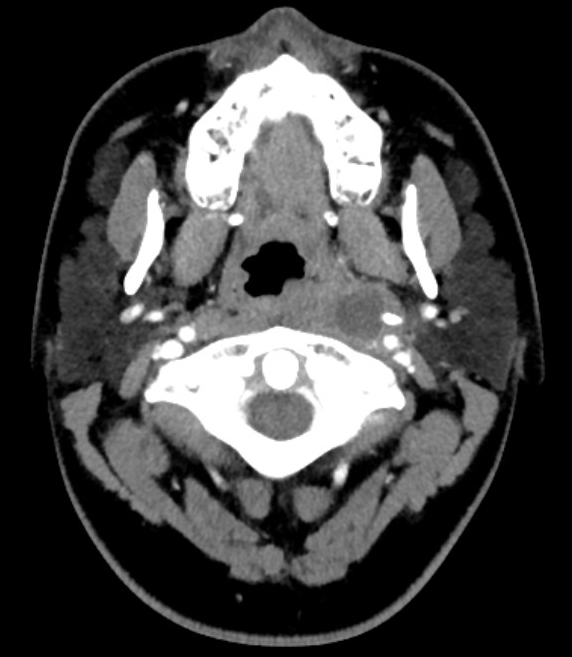

The work-up of a rapid strep test in the office was negative. The child appeared sicker out of proportion to her history and was mild-moderately dehydrated, so the patient was transferred to the emergency room. The attending and resident in the clinic felt that the patient may have a viral syndrome that would improve with fluids, viral meningitis, or less likely, a head and neck abscess. In the emergency room, the laboratory evaluation showed a white blood cell count of 18,600/mm2 with a 20% left shift in neutrophils. She had a C-reactive protein of 4.6 mg/dL. Intrvenous fluids were started and she felt better. Her head tilt continued so a head computed tomogram was performed and the diagnosis of a left parapharyngeal abscess was made.

The patient’s clinical course showed that Otolaryngology was consulted and the patient admitted. She was given intravenous antibiotics and on day 2 had surgical drainage. She was discharged on day 5 and completed 2.5 weeks of antibiotics in total. She was having no problems at followup at 2 weeks post-op.

Figure 122 – Axial image from a CT scan of the neck performed with intravenous contrast demonstrates a left sided parapharyngeal abscess with a low density, round, fluid-filled center. There was some associated mass effect on the airway.

Discussion

Deep neck space infections (DNSI) are not very common (estimated to be 4.6/100,000) but extremely important to have a high index of suspicion for.

The anatomy of DNSs is complex and covered by substantial amounts of superficial soft tissue making diagnosis difficult.

Additionally, children often cannot give more precise or accurate histories and can be difficult to examine> Most infections in children are in those < 6 years.

Lying within or adjacent to the DNS are numerous bones, blood vessels, nerves and other soft tissues. The spaces communicate between each other and therefore spreading can also occur including into the chest.

Complications of DNSI include:

- Airway compromise

- Jugular vein thrombosis (Lemierre’s syndrome)

- Mediastinitis

- Neural dysfunction

- Osteomyelitis

- Sepsis

- Vascular erosion

In pediatric patients, the usual cause is pharyngitis or tonsillitis, whereas in adult patients the usual cause is odontogenic. However it is important to note that there are substantial numbers of cases (20-50%) that the etiology is not identified. Fortunately, DNSIs are less common because of antibiotics for treatment of respiratory illnesses and odontogenic problems.

Other causes of DNSIs include:

- Cervical lymphadenitis

- Congenital anomalies

- Branchial cleft

- Thyroglossal duct cysts

- Foreign body

- Trauma

- Instrumentation – bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy

- Intravenous drug use

- Salivary gland obstruction or infection

- Laryngopyocele

- Mastoiditis

- Thyroiditis

- Malignant node or mass with necrosis/suppuration

The spread from the initial location can be from direct spread, lymphatic system, lymphadenopathy suppuration, or from communication with other DNSs. Peritonsillar abscesses (also known as quinsy) are the most common. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscesses generally are the next most common but their order depends on the study. Submandibular, buccal, and mixed infections (including Ludwig’s angina) are less common.

Evaluation usually includes some type of radiological imaging to rule out other entities and to better define the DNSI. Computed tomography is often used as it is usually available and quick to complete. Magnetic resonance imaging has better soft tissue visualization but may not be available and usually takes longer which may require sedation. Ultrasound has been used in some cases.

Patients are treated with broad spectrum antibiotics especially for mixed, polymicrobial infections with aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus are more commonly cultured. Surgical treatment is considered primary treatment and used initially or after a period of antibiotics. Some patients have resolution without surgical intervention.

Learning Point

As noted above children may have minimal signs and symptoms for DNSI. Parapharyngeal abscesses can be difficult as they can have no obvious swelling, and little or no pain or trismus. Poor oral intake, fever and upper respiratory tract infection symptoms such as rhinorrhea or cough are common and can look like many common pediatric illnesses. Fever, sore throat and dysphagia are also common symptoms of presenting DNSI patients.

Other possible signs of DNSIs include:

- Fever

- Neck swelling or mass, particularly with asymmetry

- Fluctuance

- Lateral pharyngeal wall displaced medially

- Posterior pharyngeal wall displaced anteriorly

- Tachypnea or shortness of breath

- Trismus (due to pterygoid muscle inflammation)

- Voice change

- Referred pain – ear pain, headache, neck pain

- Neural deficits – especially cranial nerves such as Horner syndrome, or vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness

- Torticollis (due to inflammation of paraspinal muscles)

Questions for Further Discussion

1. What are indications for referral to otorhinolaryngology?

2. What antibiotics would you choose for empiric treatment of DNSIs?

Related Cases

- Disease: Parapharyngeal Abscess | Abscesses

- Symptom/Presentation: Fatigue | Fever and Fever of Unknown Origin | Sore Throat

- Age: School Ager

To Learn More

To view pediatric review articles on this topic from the past year check PubMed.

Evidence-based medicine information on this topic can be found at SearchingPediatrics.com, the National Guideline Clearinghouse and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Information prescriptions for patients can be found at MedlinePlus for this topic: Abscess

To view current news articles on this topic check Google News.

To view images related to this topic check Google Images.

To view videos related to this topic check YouTube Videos.

Raghani MJ, Raghani N. Bilateral deep neck space infection in pediatric patients: review of literature and report of a case. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2015 Jan-Mar;33(1):61-5.

Lawrence R, Bateman N. Controversies in the management of deep neck space infection in children: an evidence-based review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017 Feb;42(1):156-163.

Corte FC, Firmino-Machado J, Moura CP, Spratley J, Santos M. Acute pediatric neck infections: Outcomes in a seven-year series. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Aug;99:128-134.

Hah YM, Jung AR, Lee YC, Eun YG. Risk factors for transcervical incision and drainage of pediatric deep neck infections. J Pediatr Surg. 2017 Jun 27. pii: S0022-3468(17)30396-2.

Author

Donna M. D’Alessandro, MD

Professor of Pediatrics, University of Iowa